MaltaSketches met with Jonathan Mifsud and Mario Zammit, the activists of Mqabba Santa Marija feast, to talk about what happens behind the scenes of the festa, the changing communities and overdevelopment which threatens the festa culture.

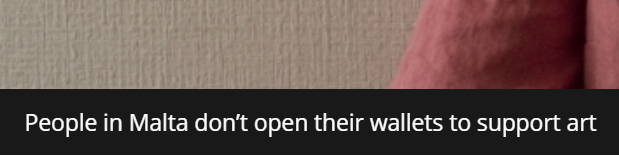

To us, the audience, fireworks is a colourful show. What is it to you?

Mario: First of all, it’s a tradition – an old tradition which has been passed from generation to generation and is especially strong in small villages like Mqabba, Qrendi, Zurrieq. It is a tradition which kept growing in strength. As children, we grew up in the spirit of feasts and fireworks.

Jonathan: The passion for fireworks and feasts begins from childhood. The older generation, those above 60 y.o. who are working at our fireworks factory, still remember the adventures associated with fireworks in those days. They used to collect remains of fireworks from the fields and play with them – something which is unimaginable today. Unlike today, safety awareness was non-existent. To some, fireworks mean burnt fingers and scars – but childhood memories are still precious.

How long does it take you to prepare to the feast?

Mario: A year and more (smiling). On 16th of August, a day after the feast, we start cleaning the warehouse. Then we estimate how much fireworks we need to sell for the coming year – our main source of funds comes from selling fireworks. We mainly sell to other feasts and sometimes – to private organisations. The profit is then distributed between 25-30 people so that they can buy the necessary materials for the next round of fireworks.

Are the workers employed at the factory full-time or are they volunteers?

Jonathan: We are all volunteers. Passionate volunteers! On Saturdays – and even Sundays – we find them working from 6 am. Persons who work in shifts dedicate all their free time to working at the fireworks factory.

Mario: And the volunteers who have a full-time job starting at 8am come to work at the factory at 5am. They are committed!

Jonathan: We have to plan rigorously and this plan corresponds to the seasonal change of weather. We prepare materials for the fireworks before February, when the weather is still cool. After February, when rain stops, petards can be left outside to dry up. Then we start assembling materials into fireworks.

In our calendar, every month marks a phase of firework manufacturing. For example, black pigment comes from vine. Vineyards in Malta are cut in January which means that January for us is the month of stocking up on vine. The stock will dry up and the black pigment will be used for the feast of the following year. Right now, we already have the vine stock for 2018. After the feast, in September, we burn vine and turn it into powder and this powder is then used during the whole year.

Correct me if I’m wrong but my impression is that all your daily routine and lifestyle is entirely tied to fireworks

Mario and Jonathan: exactly! There are so many things which are going behind the scenes and are invisible to outsiders but mean a world to us.

Firework manufacturing is a demanding process. We prepare everything from scratch, a lot of work goes into it. It would be impossible to put so much effort without passion and commitment.

Jonathan: What is also hidden behind the scenes is that many more people contribute to the process in one way or another. Farmers give us sacks, for example. Instead of throwing away empty sacks of rabbit food, they give them to us. We also collect anything which is going to be thrown away but can be re-used. So yes, we reuse and recycle (smiling)!

What truly amazes me about Mqabba Santa Maria fireworks is their precision and perfect timing. Let’s be frank: such precision and attention to detail are not common in Malta (I’m not saying it with disapproval). How do you manage to achieve such precision?

Mario: It is difficult. A firework is a controlled explosion and getting it right requires experience and knowledge of physics and chemistry. Since precision here is about splits of a second, we ensure precision of the petards’ length up to a millimetre.

Another aspect is planning and calculating it well. When we plan fireworks of elaborate shapes, we need to calculate all the parameters – distance between the petards and time of release because we cannot practice beforehand.

How do you decide on patterns? Do you all discuss them or everyone does his bit?

Jonathan: Everyone has a special role in the process so yes, we divide responsibilities. For example, I’m in charge of colour multi breaks and Mario creates day fireworks. Each one of us is a designer and manufacturer at the same time. Another volunteer creates ball-shaped fireworks and another one is in charge of a tower crane fireworks show. Everyone has his own niche where he feels most confident and comfortable and knows the process from A to Z.

How did you acquire this knowledge?

Mario: It is passed from generation to generation. Experience is precious. In order to launch a firework into the sky, we need gunpowder. Say, a 50 kg firework requires a certain amount of gunpowder. If that certain amount is exceeded, then the firework will explode on the ground whereas a fewer amount simply will not lunch it.

We also attend courses on safety held by the police. Such courses do not teach the craft per se but they instruct what ingredients should not be mixed together and what safety procedures need to be followed. We also make sure to get the ingredients from the approved suppliers which have already been tested in Spain and Italy.

Does your team have secret tricks?

Mario and Jonathan: every volunteer has his secret (laughing). Other firework factories and their volunteers have their secrets too – we all have that in common.

Another aspect which puzzles me a lot is that feasts are not mere celebrations, they are competitions of a kind. Why does festa bring on competition? Isn’t celebrating something enough?

Mario: You are right! There is a lot of pride in it. We take pride in what we do and we keep our secrets safe.

Jonathan: But this is the way it is. Taking pride in what we do and showing that we are the best is part of the drive. In the past we had to experiment much more – partially because the imported ingredients were not of sufficient quality – so every year we would do our best to establish the best possible ratio. That is a lot of effort and creativity and we ought to respect our efforts.

To be honest, this individualistic spirit rather saddens me…

Mario: Although different clubs compete when it comes to the show, it is not only about competing. We also collaborate – by sharing the firing tubes because not every fireworks factory has its own tubes. We share the firing system between four clubs as well. For example such a system costs about 10K Euro so we split the expenses between the clubs in order to afford it and everyone uses it during their feast.

What would be your life without fireworks? Say, if fireworks are banned tomorrow, what would you do?

Jonathan: No way! We would go abroad. Joking apart, our life is rotating around the fireworks and the feasts in general. Fireworks give us purpose, passion and certainty. Every month we see what needs to be done for the feast, we look forward to it. Only one week in a year – the week after the feast – is not connected to fireworks. Although even then we often go and help out at other feasts.

Is there any other club you admire?

Mario and Jonathan: Now, it’s a difficult question!

Mario: I’d say that every club in Malta develops a relationship with other clubs or organisations. We do not exist in vacuum. We are not exception in this case. For example, recently we have built a relationship with Munxar in Gozo – a village of only 700 people. Last year we produced some fireworks for their feast (just a 5 minute show) and we became good friends. We pay each other visits, invite each other for barbecues. Some people from Munxar even came to our feast and spent a week in Mqabba. We’ve developed a bond – so it’s not only about competing, it’s about friendship too… (smiling)

This is great news! You even managed to create ties between Malta and Gozo (smiling)

Jonathan: if you like to put it this way – yes. Last year, only 5 of us came to set the fireworks in Munxar, this year we were 25. You can imagine 700 Munxar people and 25 Mqabba people all crazy about fireworks. It was spectacular!

Do you think that public attitude towards feasts and fireworks in Malta is changing? Do you sense any decrease of enthusiasm or growing disapproval of the tradition in general?

Mario: Yes – and this change in attitude is not related only to fireworks. The idea of a desired lifestyle is changing a lot.

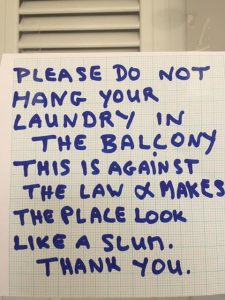

Jonathan: To me, it has a lot to do with how Mqabba community has changed in the recent years. Mqabba now has new residents who moved here from other parts of Malta and from other countries and they do not share the same passion for the feast, they do not feel being part of this culture. A German friend of mine, for instance, chose to live next to the field from which we release fireworks. The way we celebrate by setting fireworks at 8am is alien to him (smiling).

In the past we had a consensus and a shared enthusiasm. The two feasts of Mqabba used to compete with each other but the tradition itself was not threatened. Today it is no longer so.

Mario: However, the lack of enthusiasm for feasts is not only limited to foreigners. To be fair, some foreigners appreciate it more, they see it as something interesting and exotic whereas to the Maltese from the areas where festa is not prominent, say Swieqi, our work means nothing. To them, what we do is just crazy and meaningless noise.

So I would say that it’s the certain class of Maltese which disrespects festa most. They constantly complain about feasts and refuse to recognise anything positive about our work.

I agree with you. I also sense a strong wave of criticism towards the festa culture from urban middle class Maltese. One of their arguments, however, is that fireworks are not only noisy but also harmful for the environment. And this is where I disagree with them most.

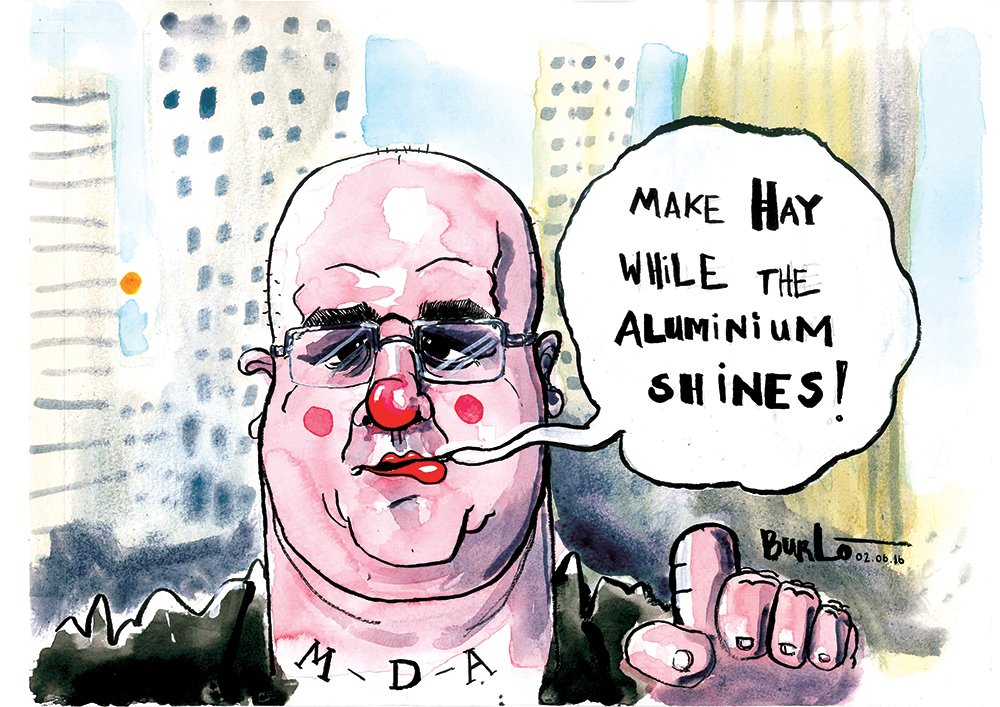

Let’s focus on development, for example. I think development of open spaces needs to be challenged collectively and a strong, united community would be able to defend itself. The areas which are most affected by the construction boom – Sliema, St. Julians, Swieqi – are the areas where community spirit (and as you’ve said, festa tradition) is practically non-existent. This weakened community cannot withstand the pressure from developers and is doomed to lose. On the other hand, feasts keep communities united and this united community can put up a fight and has a chance – and a common motivation – to win.

Mario: The increasing density of buildings – not only in Mqabba, in Malta in general – means that more and more feasts are finding it difficult to let the fireworks from the same place. Whenever buildings come too close, they have to find other open places. This creates tension. I think it is a matter of survival that all the firework clubs become united for this cause. In this case, we have a common goal and we need to join forces instead of competing.

Jonathan: I remember a case a few years ago where there was a proposal to construct a villa on an open area. This open area was used as a firework launching site. Had the permits been approved and site been developed, this firework factory would not have been granted a police permit for letting off fireworks. I recall that both the rival local village band clubs together with their Local Council and other local NGO joined forces and objected constructively to the PA together. This case illustrates that working together for a common goal is possible despite the competition between local feasts. I cannot agree with the accusations that feast clubs threaten the environment! On the contrary, we help to protect open spaces from construction.

The negative effect of the construction boom also reveals itself indirectly: this year it was a true challenge to find planks of wood to support our main firework display – they all are being used at construction sites!

Would you be interested to collaborate with the environmental NGOs to strengthen the resistance to overdevelopment?

Mario: As I have said, protecting open spaces is important to us. But the initiative should first come from Malta Fireworks Association rather than individual clubs. The Association is the voice of the firework activists in Malta.

What do you think is the future of the festa tradition?

Mario: In synchronising fireworks with music. The problem, however, is that there aren’t enough of firing systems for this type of show. We were pioneers in it 10 years ago but now every village wants to do its own pyro musical show meaning that demand and competition are increasing. But looking at the bright side, I’d say that festa tradition is still alive because it evolved and always adapted to the challenges of time.

Follow MaltaSketches on Facebook. Not to miss any posts from MaltaSketches, click the button “Following” and then select “See first”. This will mean that your feed will always contain our posts. We only post a few times a month, so you won’t see too much of us. Grazzi!

The fireworks which took a whole year of preparations are neatly labelled and stored on the factory premises .

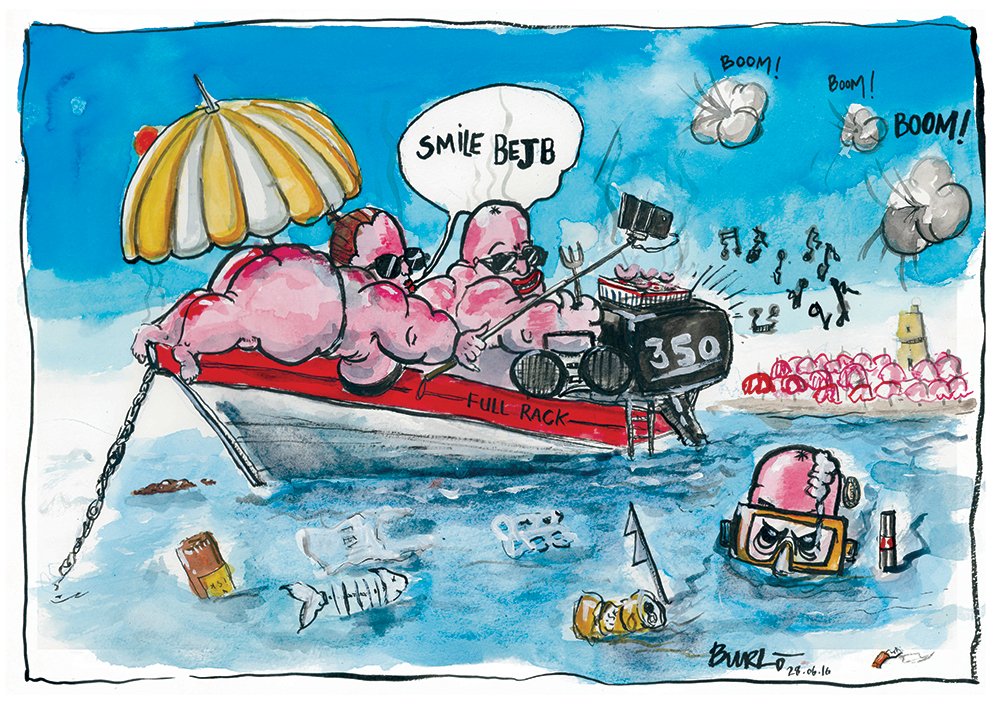

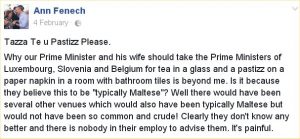

The snobbery and elitism of the PN works wonders for the PL. In fact, the latter needs a minimum effort to keep up a false display of the true leader of the common people – going to Serkin for pastizzi is enough. Never mind the reluctance to increase the

The snobbery and elitism of the PN works wonders for the PL. In fact, the latter needs a minimum effort to keep up a false display of the true leader of the common people – going to Serkin for pastizzi is enough. Never mind the reluctance to increase the

Here is the brochure “Moving Forw>ard” issued by the Government of Malta. First (but not foremost), let’s give it a credit for the sexy design. Do not worry, your government is not embarrassing you with the exposure of bad taste as you might suspect, on the contrary, the design is quite artistic. Now, if you are one of those overly sensitive individuals who put the aesthetics before the content, rejoice and read no further because further is all about the content.

Here is the brochure “Moving Forw>ard” issued by the Government of Malta. First (but not foremost), let’s give it a credit for the sexy design. Do not worry, your government is not embarrassing you with the exposure of bad taste as you might suspect, on the contrary, the design is quite artistic. Now, if you are one of those overly sensitive individuals who put the aesthetics before the content, rejoice and read no further because further is all about the content. As follows from the brochure, the government is convinced that the digital single market is a way forward.

As follows from the brochure, the government is convinced that the digital single market is a way forward.  It wouldn’t harm to ask who benefits most from this new policy. The answer is: a number of

It wouldn’t harm to ask who benefits most from this new policy. The answer is: a number of

lly was a Labour Party!

lly was a Labour Party!