A tribute to my favourite city

~ 10 minute read

Living in Valletta: a permanent surprise

When I moved to Valletta five years ago, one of my greatest surprises was seeing that particular face expression each time I told somebody where I was living. “Valletta?” – they cried, turning their face into a display of disbelief and frustration – “but why?!” It was then my turn to be surprised and reply “Why not?”, only to learn that the problem was “those-ħamalli-hostile-to-every-stranger-and-whom-everyone-in-their-right-mind-avoids“, or, in brief, the stereotyped residents of Valletta. I usually replied by admitting that I had not noticed anything outrageous about my Valletta neighbours, compared to my previous neighbours in Msida and Gzira, and used to receive a skeptic look, followed by a short yet affirming “not yet”.

Although so much has changed in five years, ironically, the expression of surprise accompanying the question “Do you live in Valletta?” remains, but of a different kind. The alarmed look has now been replaced by a brow-raising suspicion of my riches. The most frequent question now is “How can you afford it?” This curiosity is easily understood: at this point in time, the monthly rent for a basic two-bedroom property is no less than €700, whilst more fashionably furnished properties cost between €1000 and €2300 (!) per month.

What’s happened? How has the capital so closely associated with “slums”, “criminals” and “ħamalli” become trendy and barely affordable for an average earner within just a couple of years? One way to answer this question is simply the effect of gentrification brought on by handsome property investment prospects as part the European Capital of Culture 2018. However, the side effect of the approaching V18 is only part of a bigger picture. In fact, rather than being smoothly revamped into a “capital of culture”, Valletta 2017 has become much more of a battleground between antagonistic cultures and the winner is the one which promises highest profits.

What is Culture?

The rapid transformation of Valletta is a source of many disputes. Some argue that Valletta is far more charming in a crumbling state, whilst others say that a facelift is necessary due to the hosting of the European capital of culture. One way or another, the ultimate majority of discussions about the future image of Valletta focus exclusively on the visual aspects of its facades and omit the stories of human relationships hidden behind them.

To start with, there is no universal definition of culture. In fact, the two most frequently referenced definitions contradict one another. According to one of them, culture is “a moral and aesthetic ideal, which found expression in art and literature and music and philosophy”. This definition is attributed to Matthew Arnold and his work “Culture and Anarchy”. The other author, Edward Burnett Tylor, suggested that culture is “that complex whole which includes knowledge, belief, arts, morals, law, customs, and any other capabilities and habits acquired by man as a member of society”.

The fate of Valletta depends on which kind of culture it is going to be a capital of. Is it the culture limited to prestigious entertainment or is it the culture of everyday life experiences which bring the place and the people into a tangible bond? Is it the culture which only sees Malta’s capital as a gourmet backdrop for trendy performances or is it the culture which can be experienced only by becoming part of its daily fabric?

Valletta as two cities

I always thought that every place owns its unique spirit to the indissoluble relationship between its architecture and its people. However, soon after having become a part of Valletta myself, I began to realise that, in the eyes of the public, Valletta was two distinct things: one – a marvel of Baroque architecture and the other – a swamp. One – to be admired, the other – to be disdained and vilified. One – its facades and the other – its 3rd class residents.

I learned that Valletta was severely bombed during World War II and the majority of its A-list residents fled to safer places. Countless times the elegant ladies and gentlemen shrugged, spreading their hands to indicate disapproval and telling me “Valletta was a city built by gentlemen, for gentlemen … and look what it is now!”

The tragedy of this immensely charming city is that Valletta’s architecture and Valletta’s residents are not recognised as one coherent whole. Sadly, in the eyes of respectable citizens and heritage guards such Din L-Art Helwa, the residents and the architecture belong to different dimensions and worth of contrasting treatment. The residents, often stereotyped as primitive boors, leeches depleting the social welfare or criminals, are presumed undeserving of the places they inhabit, in which every stone tells a story of its past noble magnificence.

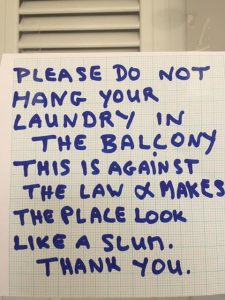

The Maltese gentry, for whom culture and Baroque are interchangeable terms, goes at lengths to emphasize that the city built by their forefathers still belongs to them and it should be reserved for worshiping high culture. They denounce anything unfitting of Valletta’s noble image. The Monti, pastizzi shops, clothes lines – everything inseparable from the daily lives of many of Valletta’s residents – is classified as desperately brutish, plebeian and culture-lacking. The social housing units of Mandragg and lower Valletta fall into the same “shameful eyesore” category.

Hipster Valletta: regeneration with a taste for venerating poverty?

Unfortunately, the nation-wide pride of its architecture did not protect “the city built by gentlemen” from decades of neglect. In his renowned photographic essay “Vanishing Valletta”, David Pisani documented the crumbling abandoned buildings which neither “gentlemen” nor the government rushed to restore. The most beautiful facades were not deemed worthy of care until a few years ago, when shabby suddenly became the new chic. New bars on Strait Street and lower Valletta (former red light districts) were injected with a new vibe. However, these trendy outlets rely mainly on the fashionable hipster crowd who visit Valletta for a sip of “authentic experience”.

The hipster crave for “authenticity” deserves a special mention. Unlike the conservative baroque-worshipping gentry, the predominantly young creative middle class is not repelled by shabby walls and laundry lines. On the contrary, the youth unfamiliar with the realities of true undignified poverty sees dilapidated spaces as aesthetically pleasing and “cool”. Thus, to the hipster culture, Valletta’s crumbling facades are a splendid backdrop for a trendy party.

The hipster culture does not seek a deeper relationship with the city because its interests do not go beyond the aesthetics of the facades. This way of experiencing the city also deprives its residents of their humanity as it folklorises them into exotic creatures. The condescending acceptance of embarrassingly styleless specimen best manifested itself in a LovinMalta’s article: with a touch of sentimental sadness, it waved good-bye to the Triton Fountain kiosks, classifying them as amusing, yet unfitting to the upscale image a European Capital of Culture is expected to flaunt.

The contrast between the outspoken poverty of a few Valletta’s neighbourhoods and the trendy entertainment culture thriving on romanticising this poverty is stark. Hipster’s willingness to hang around dilapidated spaces sets a precedent for opening of more bars designed to suite a particular taste. While Tico-Tico, Café Society and the Gut physically belong to Valletta, they remain an isolated bubble which overlooks the life of the local community.

However, my skepticism towards the hipster attitude to Valletta does not extend to criticising all of the younger vibes. On the contrary, Valletta’s population is ageing, which means that many more houses will become vacant in the near future. Will these houses be reborn as homes or will they turn into outlets whose only contribution to Valletta’s life is commerce?

Boutique hotels for the tasteful caste

The handsome profitable prospects brought by the European Capital of Culture have turned Valletta into a goldmine and a battleground between various interests at once. After the decades of neglect and distant worship, the vacant houses and residential properties discovered a new meaning of existence – that of a boutique hotel.

It is easy to lose count of the permit applications for boutique accommodation popping up practically around every corner.

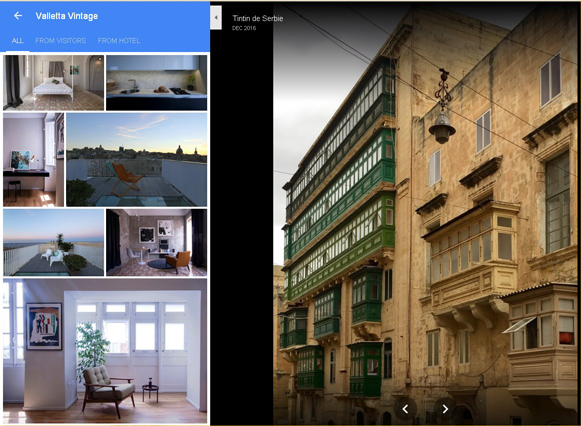

With no exaggeration, there soon will be more boutique hotels than residents in Valletta: exclusive accommodations such as Ursulino, Casa Ellul, SU29 and Palazzo Consiglia are now competing for distinguished clientele with La Falconeria, De Vilhena, Valletta Boutique Living, Valletta Vintage and a dozen more boutique hotels-to-be at Republic, St. Paul’s, St. Christopher, St. Ursula, St. Barbara, Old Theatre, Old Bakery Streets and Valletta’s old fish market Pixkerija. Barbara Bastions can now be safely renamed into Boutique bastions since only a couple of houses in that location are not being converted into exclusive accommodation of some kind.

The construction works were criticised by the local council as “the worst siege ever” and slammed by the residents, the heritage organizations and the intelligentsia alike – albeit for contrasting reasons. Whereas the residents have to endure the non-stop sounds of drilling, the cranes above their roofs and the clouds of dust, the reasons for critique from the heritage activists and the creative class are not as straight-forward. It is not the appropriation of residential houses into boutique hotels that the “baroque or nothing” heritage activists protest, but the obscure appropriators whose cultural unawareness and opportunism are enough to infuriate the gentry. The creative crowd predictably protests the visual aspects of the developments: the cranes distorting the skyline, the disappearance of venerated shabbiness and the heavy presence of scruffy workers, so unpleasant to the aesthetically sensitive taste.

On the other hand, the ever-growing number of boutique accommodations provides a perfect opportunity for implementing interior designer skills and entrepreneurial ambitions – the traits highly respected by the tasteful critics. Thus, once the cranes, the trucks and the workers are gone leaving behind a new deliciously designed hotel, the critique is immediately replaced by ovations and excitement at the prospects of welcoming the esteemed guests. Gentrification of Valletta is not only barely spoken about but is openly celebrated. Same is true about the Three Cities – Senglea, Cospicua and Birgu.

It certainly is positive that the buildings of such beauty and history are being restored, yet it is equally sad that the restoration of these buildings is deemed worthy only if it promises solid investment rewards. Besides, the “boutiquefication” of Valletta reduces the residents and the everyday life to a decorative view from a holiday room.

The Capital of Whose Culture?

Another unsubtle declaration of what kind of culture is to be respected came from the artistic director of Teatru Malta, Sean Buhagiar. A few months back, when snap elections were not on the horizon, he urged the Prime Minister to abstain from disturbing the “culture” with such an uncreative event as general elections. Sadly, this point of view is shared by the various creative professionals – artists, designers, performers – to whom Valletta 2018 is, first and foremost, an opportunity to impress an eminent international audience with the presumably high degree of creativity .

The employment and career opportunities offered to a broad category of professionals by Valletta 2018 are certainly among its positive aspects, yet the statements like those said by Sean Buhagiar are indeed irritating, because they refuse to acknowledge any other definition of culture except from artistic performances which he and his colleagues play an imperative role in. Indeed, the demand for sophisticated entertainment is at the core of the middle- and upper-class cultural habits yet culture, in its broad sense, is not equivalent to the consumption of concerts, performances and exhibitions.

Sincerely, I have lost count of various Valletta-related arguments to disagree with.

I disagree with sentimental conservationists who morn the Valletta of crumbling facades and regard it as far more dignified than Valletta restored. While shabbiness might appear particularly spiritual to spectators, to many residents it simply signifies poverty and the inability to carry out restoration works on their own.

I disagree that the only way to restore Valletta is to convert it into a host of exclusive guest houses for the privileged caste, trendy bars and luxurious shopping outlets. The Valletta of boutique hotels would be hollow and soulless. The void of community spirit, which makes every city so unlike any other, would be replaced by temporary visitors who don’t have a profound relationship with the city. It would turn locals and their households into somebody’s room with a view. Yet, how can Valletta resurrect as a city with its own vibrant community life, if properties here are out of reach for the majority of the Maltese population?

Finally, I disagree with reducing Valletta to a backdrop for upmarket entertainment and tasteful consumption wrapped into “the European Capital of Culture 2018” package. As any other place, Valletta does not lack culture of its own. On the contrary, it has plenty of it – the little mundane rituals of “hello” and “how are you”, the feasts, the relationships between the people whom Valletta comforts and makes feel at home. Unlike the pre-packaged commodified experiences offered by hipster culture and Valleta 2018, the culture of daily participation cannot be exhibited at a museum or performed on stage – it cannot be experienced in any way other than becoming a part of its fabric. Too bad this kind of culture does not offer profitable returns and hence is not held in high regard.

Follow MaltaSketches on Facebook. Not to miss any posts from MaltaSketches, click the button “Following” and then select “See first”. This will mean that your feed will always contain our posts. We only post a few times a month, so you won’t see too much of us. Grazzi!